Presented by ONETrack International, Berkeley

By: Vani Gupta, Alexandra Garcia

Prior to the Kosovo War, the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia had autonomy over the region of Kosovo which led to a group of Kosovo Albanians forming the Kosovo Liberation Army as an act of rebellion. The first actions of the KLA against the Yugoslavian government began in 1995 and year after year, there was even more defiance against Yugoslav rule and war broke out between the two sides. Eventually the Yugoslavian federation separated into several autonomous regions. Much of the discrepancies between the two countries that resulted in a full on war are further explained in vast detail (below ‘Background’).

As the war came to an end in 1999, Kosovo became more economically independent. Kosovo has managed to expand their exports in order to better support and build their economy. Kosovo’s growth in the industrial market paved the way for their foreign trade market to prosper and this rapid economic change resulted in an artificially inflated economy. Unfortunately, with an artificially inflated economy came several consequences such as human trafficking and prostitution. Although Kosovo was partially independent from Yugoslavia, the Albanian population became a prime target for human trafficking and since the end of the war, human trafficking in Kosovo has only progressed.

In addition to the changing economy, human trafficking in Kosovo ironically increased despite the foreign peacekeeping efforts. The ethnic divide between Kosovo Serbians and Kosovo Albanians that developed from the war had intensified to the point where it had to be met with foreign intervention. Peacekeeping efforts in the form of the United Nations’ Kosovo Protection Force (KFOR) and NATO began to take place. At its largest, over 50,000 peacekeeping KFOR troops were present in Kosovo. By 2001, foriegn soldiers made up about 2.4% of Kosovo’s population. There has been much speculation that the presence of so many foreign forces and soldiers have been a major factor in the increased demand for prostitution and sex work, with many organized prostitution sites set up in locations very close to KFOR troop bases. The increase in sex work in Kosovo entailed a higher need for human trafficking, thus deepening the issue.

While the economic aftermath of the Kosovo War and foreign intervention had escalated human trafficking, the uncertain political state of Kosovo perpetuated the issue. By 2000, Kosovo had become a major destination for human trafficking, as human rights organizations such as UNIFEM began raising their concerns on the government’s approach to fixing the problem. From 2000 to 2002, the International Organization for Migration had reported helping victims of up to 303 trafficking cases in Kosovo.

Kosovo’s declaration of independence from Serbia in 2008 has also had a tremendous impact on its human trafficking issue. Kosovo’s newly gained independence meant that the country had to tighten its borders, leading traffickers to find victims within Kosovo rather than from abroad. Rather than being a destination point for human trafficking, due it its independence Kosovo became a place of origin. The steady rise of internal trafficking within Kosovo can partly be recognized as the doing of organized criminal groups.

Many of the victims of human trafficking in Kosovo face sexual exploitation and are coerced into prostitution. Much of the prostitution takes place at establishments such as nightclubs, restaurants, and massage parlors—to disguise their role in trafficking actions. Today, the typical profile of a trafficking victim in Kosovo is that of a young female under the age of 18, often unknowingly manipulated into the system.

In terms of institutional responses on the international front, Kosovo has consistently remained in the Tier 2 category of the US Department of State’s Annual Trafficking in Persons Report. Tier 2 countries are acknowledged to be those which are not fully compliant with the US’s Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act, but are recognized to have made efforts. Moreover, international monitoring reports have been implemented within European countries to ensure that these institutional efforts continue. Examples of these efforts in Kosovo specifically include enforcement of police and action plans created by the country’s Ministry of Internal Affairs. Though efforts have been made to better the issue, much criticism is still present, especially for Kosovo’s judiciary system. Many have criticized the low sentences that convicted traffickers face; the Kosovo’s Criminal Code prescribes a 5 to 12 year sentencing, many of those convicted only end up serving between 7 to 18 months. Shelters have been provided for human trafficking victims in Kosovo, with two being dedicated specifically to victims of sexual exploitation, and another dedicated to child trafficking. These shelters are run by non-governmental organizations (NGO), and are unfortunately severely underfunded.

Despite the issues the shelters face, it is clear that Kosovo has taken great strides to address the human trafficking issues that have prevailed throughout the country since the end of the Kosovo crisis in 1999.

Background: Kosovo

By Paris Viloria, Yesica Martinez

Since 1999, controversy surrounding the independence of Kosovo has prevailed in contemporary international relations debates. Despite the debates prolonging the legitimacy of Kosovo’s independence, it is important to acknowledge how the history of Albanian and Serbian ethnic conflict continues to play a role in the current efforts of state building of Kosovo.

Kosovo’s population has long been dominated by Albanians as the majority, with the 1921 Yugoslavian Census report 64.1% Albanians to the CIA reporting 92.9% of Albanians in 2021. Around World War 2, ethnic tension among Serb and Albanian communities prevailed in the south-eastern European region now known as Kosovo. After the Cold War, the fall of the USSR paved the way for multiple ethnic groups on the former eastern front to seek sovereignty, with countries such as Slovenia and Croatia declaring independence, and Kosovo Albanians having newfound hope for independence.

With Milosevic as the new President of the Serbian League of Communists, many followers of politics in the Balkans observed what they considered a dramatic rise in Serbian nationalism. Milosevic had a strong stance towards the Serbian people and sought to dominate Kosovo’s administration. When the Albanian population dramatically grew, an increase in ethnic enclaves, diversity of religion and linguistics, and pluralism replaced most of ethnic concentrations. These expulsions have continued throughout the years from both ethnic groups. In effect leading to the persecution of either ethnic groups prevailed high across the region with what could be perceived as an aim to cleanse or kill those of the opposing ethnic group.

The tension between ethnic groups escalated with the administration of Slobodan Milosevic in 1986. Under the League of Communist of Serbia, Milosevic ran under a political campaign that aimed to protect the minority ethnic group of Serbs from the Kosovo Albanian majority. Milosevic took steps to dissolve the Kosovo Albanian assembly and governance by giving Serbian officials control over the administration of Kosovo, an act that many have called “Serbianisation.”

Some of what has been considered Serbianisation includes dominating court and civil defense, banning Albanian as a language of primary school instruction, developing initiatives to close down Albanian media platforms as well as higher education accessibility, and even renaming infrastructure and streets into Serbian names. Thousands of Albanians lost their jobs as many belongings, savings, and even companies of Albanians were confiscated during this period. Reports of violence towards Albanians included police violence, home searches and arrests, local conflict, and high unemployment towards Albanians.

The rise of unemployment led to a limitation of resources for Albanians as many services were no longer available and those that were public were a high concern of safety. As a result of what was seen by many Albanians as Serbianisation, an underground Albanian society grew to overcome social disparities caused by segregationist policies where Albanians went to their own underground schools, created underground businesses, established their own private health clinic, and much more, ultimately creating separate societies.

In response to the heightened violence towards the Albanian population under Milosevic’s regime, political opposition grew. Ibrahim Rugova, under the Democratic League of Kosovo, peacefully opposed Milosevic’s policy and rule with a large support of Albanians. Rugova sought peace among the tensions by lobbying international involvement in the legitimacy of the Serbian rule and urged Albanians in Kosovo to refrain from violent resistance. In addition, he boycotted Serbian elections by establishing a shadow government to hold elections incorporating Albanians. Rugova’s peaceful resistance against Serbianisation failed as the Serbian authorities continued to use force in the Kosovo region.

Despite the various efforts to overcome the violence that prevailed in Kosovo, tension grew and military presence grew from both parties. Between 1996 and 1997, the formation of the Kosovo Liberation Army led by Albanians expanded. Small guerilla groups formed and attacked Serbian police officers as part of their resistance movement. This military group attacked Serbian officials and police officers. In response to the growing presence of Albanian led formation Serbian forces started a campaign of systematic destruction of Albanian villages in the summer of 1998 under the command of President Milosevic, as part of what most of the international community has labeled ethnic cleansing operations. The result of the formation from both parties led to an increase of unlawful killings and human rights violations, and ultimately the Kosovo War in 1999. This war ended after a year when NATO’s 78 day long airstrikes forced Milosevic to withdraw his forces in Kosovo and establish UN peacekeepers within the area. In light of growing conflict, the UN proposed the Security Council Resolution 1244 in 1999, that transferred peace keeping force to NATO to virtually suspend Yugoslavia sovereignty to Kosovo

Attempts to decrease the violence in the international field gained recognition in 1999 through EU’s help with Kosovo’s economic, political and social transition and transformation. In 2008, the EU launched EULEX, a legislative body to set forth stability and rule of law, with the Kosovo Albanian delegation to secure Kosovo’s independence. Previously Kosovo was not considered an independent state, as it did not meet UN protocol (and today is only recognized as a legitimate state by around 100 countries). This was done through the transition and formation of a new legislative body that would mediate inner conflicts. By February 18th, 2008, Kosovo declared official independence under Fatmir Sejdiu, the first president of Kosovo.

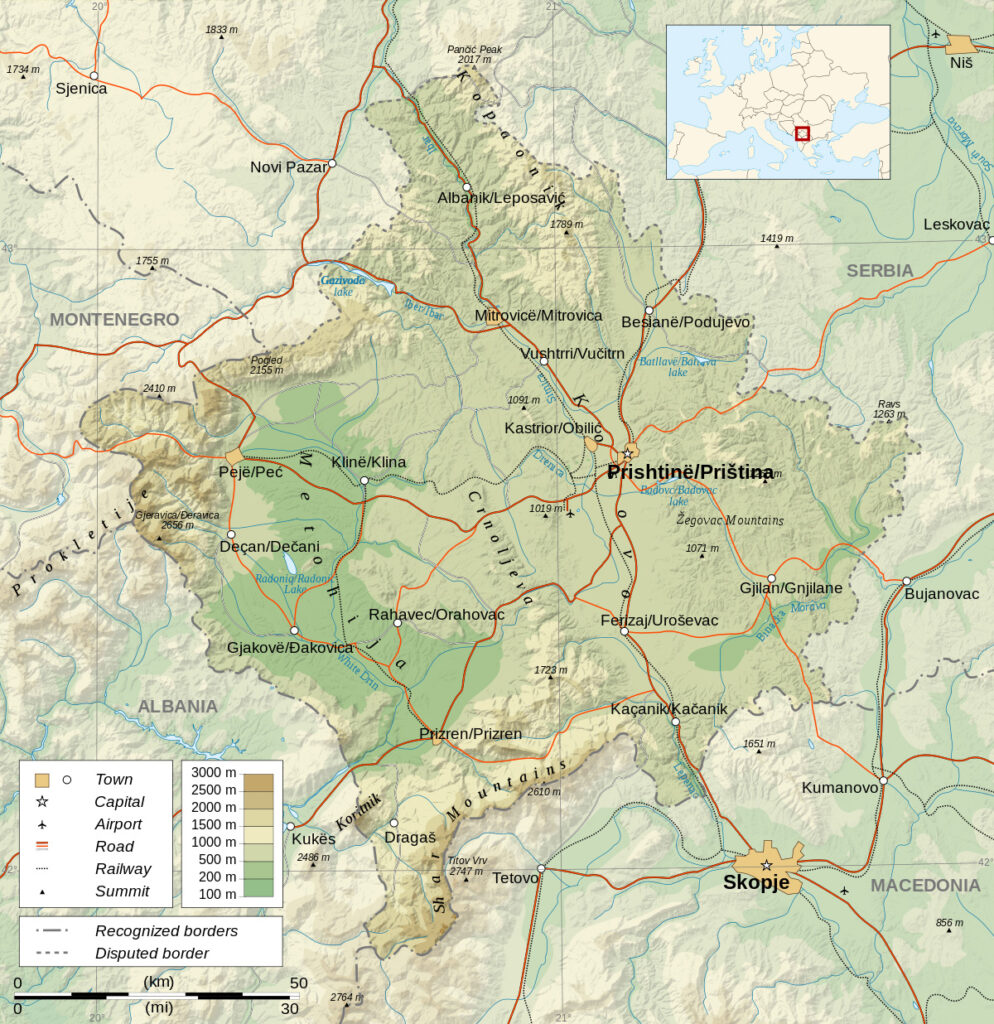

The history behind Kosovo’s independence has largely shaped the current trajectory and state of the country. Ethnic tension after independence still largely prevails in Kosovo and is largely remembered by many individuals residing in Kosovo. Many accounts from Kosovars living during these times include reports of the disappearance of children and women, rape and more. The ethnic demographics and concentration reflect those during the war. Most northern cities during the war were populated by Kosovo’s Serbs, now about 90% of Serbs live in enclaves in central, eastern and northern parts. Other ethnic communities largely live in rural areas. Economically, Kosovo’s population has an average consumption cost divided between rural and urban. Rural areas have an average of 7200 euros per family and 8000 euros per family in urban areas. A large budget from families living in rural areas comes from food and transportation rather than health and education. The economic trajectory of Kosovo is important to recognize in light of its history as it remains to be the poorest european country.

There has been a rise of child labor, human trafficking and levels of poverty in Kosovo. In response to these conditions, concern has risen among the Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare of Kosovo. Initiatives towards community-based services with Hope and Homes for Children have aimed to provide social services for children at risk of living in vulnerable spaces. ONETrack International is helping by implementing its reintegration system.

Bibliography

“ANALYSIS OF THE SITUATION OF CHILDREN AND WOMEN IN KOSOVO (UNSCR 1244).” UNICEF, UNICEF , Oct. 2017, www.unicef.org/kosovoprogramme/sites/unicef.org.kosovoprogramme/files/2019-01/Raporti_unicef_ENG.pdf.

Chadwick, Lauren. “A History of Tension: Serbia-Kosovo Relations Explained.” Euronews, Euronews., 15 July 2019, www.euronews.com/2019/05/28/a-history-of-tension-serbia-kosovo-relations-explained.

Crowcroft, Orlando. “20 Years on, the Disappeared Still Cast Shadows in Northern Kosovo.” Euronews, Euronews., 3 Mar. 2021, www.euronews.com/2021/03/01/for-kosovo-s-serbs-the-fate-of-the-disappeared-looms-large-20-years-on.

“The Development of Kosovo and Its Relationship with the EU.” Econstor, Institute for European Integration, 2015, www.econstor.eu/bitstream/10419/110956/1/827020082.pdf.

DICK, LEURDIJK DICK ZANDEE. KOSOVO: from Crisis to Crisis. ROUTLEDGE, 2020.

Haxhiaj, Serbeze. “Kosovo’s Invisible Children: The Secret Legacy of Wartime Rape.” Balkan Insight, Balkan Transitional Justice, 9 July 2019, balkaninsight.com/2019/06/20/kosovos-invisible-children-secret-legacy-of-wartime-rape/.

“Kosovo – The World Factbook.” Central Intelligence Agency, Central Intelligence Agency, www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/kosovo/#people-and-society.

Kupchan, Charles A., and Ivo H. Daalder. “If No Ground Troops, NATO Should Cut Its Losses.” Brookings, Brookings, 28 July 2016, www.brookings.edu/opinions/if-no-ground-troops-nato-should-cut-its-losses/.

Rukovci, Eurisa. “The Rural-Urban Divide in Kosovo.” Lefteast, LEFTEAST, 9 Sept. 2016, lefteast.org/the-rural-urban-divide-in-kosovo/.