Written by Allegra Lleo

To some, home is a roof, four walls, a bed, and the reassurance that they will have a place to rest their head when night falls. To others, home is not a place, but a sentiment. A sentiment that no place, four walls, and a roof could replace. A sentiment rooted in culture, family, belonging, and familiarity. For orphaned children, a consistent and stable home is not always guaranteed. The idea of home, changes, at times far away and hard to grasp. Family, heritage, roots, and community are all words, feelings, ideas that should not be taken away from them, even if their home is no longer the walls that once surrounded them.

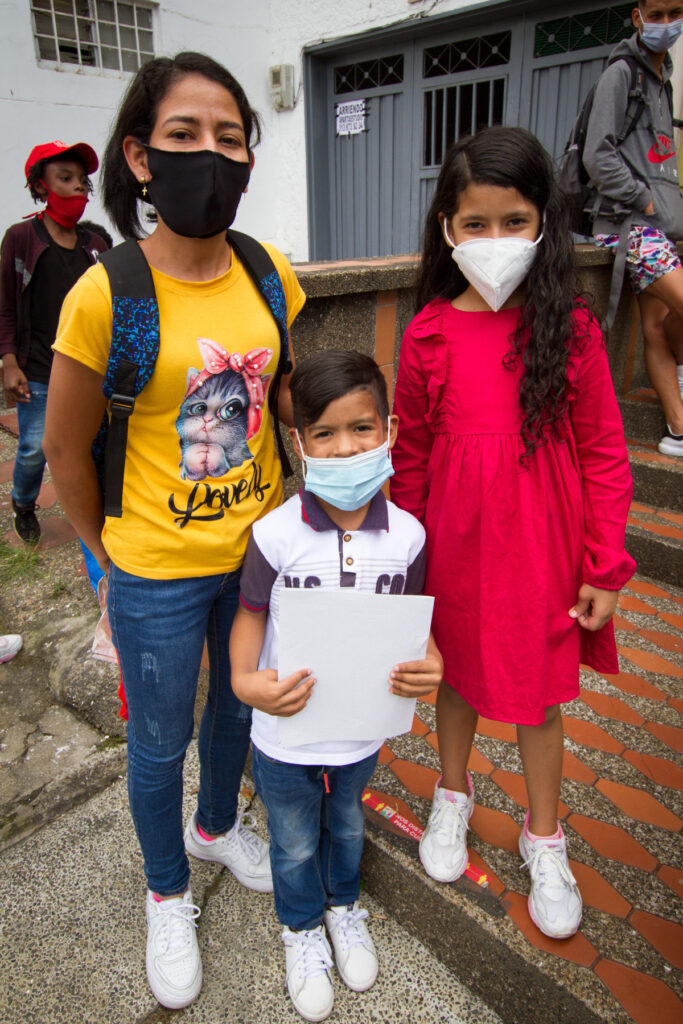

With the help of organizations such as ONETrack International, children no longer feel like they’ve lost a home. Being relocated to extended families, and cities or towns where they grew up, can ensure the sentiment remains, even during the hardest times. A song from their hometown, a recipe passed down generations, a tradition that reminds them of a memory long ago, all these little things will shine a light on their new home.

Heritage is “the traditions, achievements, beliefs, etc., that are part of the history of a group or nation.” Why is heritage so important to those who have lost their immediate family? Beyond genetics and bloodline, the deep-rooted values stemming from background and culture, are what truly distinguish one family from the next. Heritage gives people a place, even when they no longer have one. It is a reminder of what they may have lost, what they long to find again, and what makes them who they are.

The social construct that is “home,” means different things to people all over the world. How does a house become a home? In an inquiry project conducted of transnational youth in South Philadelphia, studying the concept of “home,” amongst young adults, the studies demonstrated that “most students, for example, drew on experiences with their immediate families in South Philadelphia to emphasize how cultural elements such as the food, music, and practices of their transnational, multigenerational networks featured in their conceptions of home.” Furthermore, the study concluded that the youth drew on their ancestors as a way of understanding and interpreting their idea of home. “He observed that “home is a community where you feel supported.” Still, others meditated on how their ideas about home connect to the broader legacies of ancient cultures: Odalys, a junior in high school and of Mexican descent, sketched a yellow pyramid that represented the “precolonial past” of her family. In her final piece, this ancient image is juxtaposed with “modern” urban images, suggesting an interplay of space, time, and ongoing legacies of coloniality in her personal vision of home.”

This opens up the discussion of what it means to belong. Even through art, young adults include their ancestorial ties in not only depictions of their home, but their identity. It is easy to believe that ancestors have been long forgotten, when in fact, they have become one of the biggest points of both unity and separation. Ancestors relate to one’s heritage, creating a deep-rooted sense of belonging. Whether heritage creates such great admiration that it brings communities together, or such difference from other heritages that it creates segregation, within itself, it is a home. An unattainable home, that houses those of its kind, giving them a place to belong.

Belonging to a community where all is familiar, can be a guiding light for those looking for a place to call home. One may even call it an instinct, similar to the homing instinct in animals. Homing is “relating to the ability of some animals to find their way home,” according to the Cambridge Dictionary. If this is such a basic instinct in animals, do humans have the same instinct to return to a place they consider home? To further understand the homing instinct in animals, professor S. Mandal wrote an article regarding these behaviors. “Abstract Performing efficient homing, i.e., returning to a previously known place, is crucial for the survival of any motile animal. Animals perform homing across different spatial scales and environments, employing various mechanisms with the aid of different sensorimotor systems molded by their varied evolutionary histories and ecological constraints. Despite these differences, most of the homing mechanisms across different taxa can be explained by some general basic mechanisms.”

The importance of an animal returning to its point of familiarity forces us to contemplate the need for humans to return to theirs as well. Does tradition, family, and communal environment become that point of return for those without a home? No matter how far they have strayed, grown, and uprooted their lives, they will always find a way back to the place that once was their home.

Even for children who have not lost their families, a childhood home can be much more significant than any other. Again, representing a point of return for many, the childhood home, is a big indicator of what “home,” represents to people all over the world. It is a representation of our past, one that is longed to be remembered and relived. Despite coming from different backgrounds, lives, and beliefs, everyone shares an inner child. An inner child that begs for love, hope, and kindness. A house that once embodied all of those things quickly becomes a home; no longer a place but a memory that is searched for by so many, wherever they may go. “We often want to check in on the places where we once lived. A third of American adults have visited their childhood homes in what Jerry M. Burger, the author of Returning Home: Reconnecting with Our Childhoods, describes as a “widespread phenomenon.” We may take these journeys because we want to remember our youth — and what better way to do it than by walking around a house that’s no longer yours?” Ronda Kaysen wrote in her article ‘Can You Go Home Again?’ for The New York Times ‘”There is this need to feel that your childhood still exists in your memory and it’s an important part of you,” said Burger, a professor emeritus of psychology at Santa Clara University,” she explains, as she dives into the connection between a person and their past life.

Orphaned children, not only search for a place to feel safe but a place to feel nourished with love and care. The reunification of orphaned children with extended families is the key to preserving the sentiment of home. By offering an alternative to orphanages through this process, orphaned children will no longer lose the fundamentals of the home they grew up in. Children can learn and grow, in a safe and familiar environment. Taking the time to reunite orphaned children with not only their families but heritage and community, goes a long way when achieving the feeling of a true home. Bringing back fond memories, important traditions, and most importantly a feeling of belonging in a place representative of their home can be a great light for any child struggling through the foster care system.

The word “home,” will always change. Throughout the years, in different countries, to certain people, home may never represent that same concept. Both negative and positive memories can quickly shift one’s perception of a home. For those that have little, a home can be their greatest achievement. For those that have much more, a home may just be a place to rest their heads. Regardless of how much or how little a person has, much deeper rooted than a structure, home is a representation of hope. Hope that those traditions, memories, and moments so familiar will remain. Home is hope, love, and most importantly, family.

References

“Heritage Definition & Meaning.” Merriam-Webster. Merriam-Webster. Accessed December 3, 2021.

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/heritage

Gultom, Frianna, Faustine Gultom, Marco Kosasih, Minghui Li, Jasmine Lie, Christopher Lorenzo, Frederick Hidayat, et al. “What Is Home? A Collaborative Multimodal Inquiry Project by Transnational Youth in South Philadelphia.” In:Cite Journal 2 (June 26, 2019): 4–24. doi:10.33137/incite.2.32826.

“Homing.” HOMING | definition in the Cambridge English Dictionary. Accessed December 4, 2021.

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/us/dictionary/english/homing

Mandal, S. “How Do Animals Find Their Way Back Home? A Brief Overview of Homing Behavior with Special Reference to Social Hymenoptera.” Insectes Sociaux 65, no. 4 (October 16, 2018): 521–36. doi:10.1007/s00040-018-0647-2.

Kaysen, Ronda. “Can You Go Home Again?” The New York Times. The New York Times, October 4, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/04/realestate/can-you-go-home-again.html.